At some point, I stopped trying to improve agents.

Not because they are bad, but because they fail in very predictable ways, regardless of the model, prompt, or role.

The problems always looked the same:

- an agent hangs and goes silent

- an agent "thinks" forever

- a pipeline breaks in the middle

- retries turn into chaos

- after 20 minutes, it's unclear where things are stuck

Trying to fix this with more "intelligence" didn't help. Planners, self-reflection, better prompts — all of that looks nice, but it doesn't make execution reliable.

A shift in perspective

Eventually, I stopped treating an agent as an intelligent entity.

I started treating it as a process.

A process has a few objective signals:

- it is running or it is not

- it produces output or it is silent

- its log grows or it doesn't

- it exits with code 0 or with an error

Everything else is interpretation.

If an agent doesn't write to its log, I don't care whether it is "thinking" or stuck. From the system's point of view, it's the same thing.

Agent as a Unix process

I ended up with a very simple contract:

- an agent is an executable

- it accepts arguments

- it writes to stdout/stderr

- it returns an exit code

That's it.

No special trust. No assumptions about honesty or self-awareness.

If it hangs — it can be killed. If it crashes — it can be restarted. If it lies — that's irrelevant, I only look at physical signals.

Why a DAG instead of a chain

Linear chains of agents are fragile.

Real workflows almost always look like this:

- some steps can run in parallel

- some must be synchronized

- some stages are optional

- others are critical

A DAG is not about "workflow tooling". It's about constraining chaos.

It answers simple questions:

- what must happen first

- what can happen in parallel

- where things converge

- what counts as success

Without this structure, pipelines slowly drift into undefined behavior.

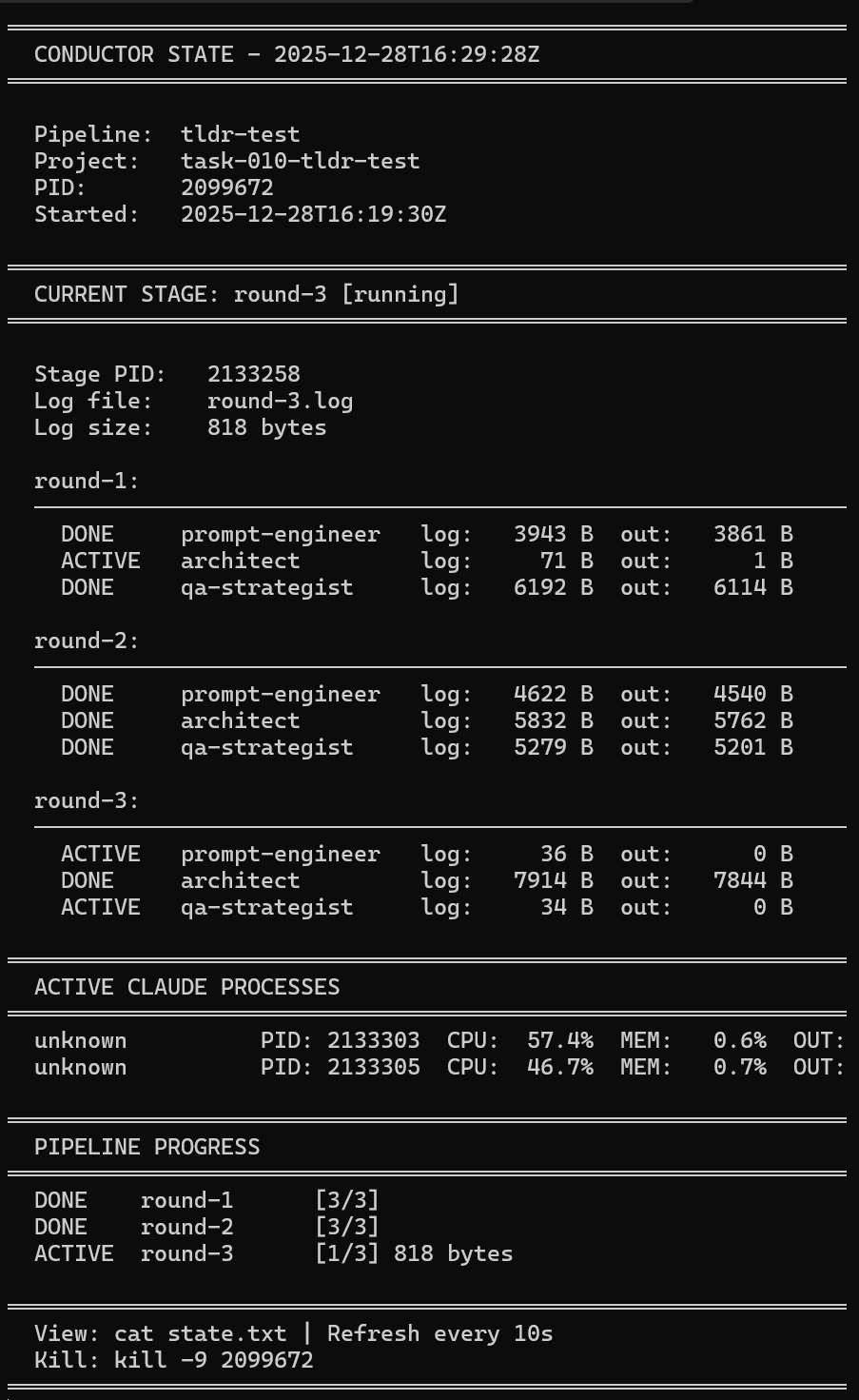

The watchdog matters more than orchestration

The most important component in the whole setup is not the DAG.

It's the watchdog.

The watchdog doesn't ask the agent how it feels. It doesn't read reasoning traces. It doesn't trust reported status.

It looks at facts:

- is the process alive?

- is the log file growing?

- when was the last update?

If the log doesn't change for several minutes, the process is considered stalled. It gets killed and restarted.

This is crude — but it works.

Why YAML and not more code

I didn't rewrite agents into a unified framework.

Instead, I described execution in a manifest:

- which command to run

- with which arguments

- what it depends on

- where it logs

- how long it is allowed to run

YAML describes what happens, not how it happens.

All execution logic lives in the orchestrator. The manifest stays declarative and versioned.

If the pipeline changes, the YAML changes — not the agents.

A minimal mental model

Visually, the idea looks like this:

The orchestrator decides what should run. The watchdog verifies what is actually happening.

What this is not

To be explicit about the boundaries:

- this is not an Agent OS

- not autonomous agents

- not a reasoning framework

It's an execution and supervision layer.

It doesn't make agents smarter. It makes the process predictable.

Closing thought

I didn't try to solve reasoning.

I solved a simpler problem:

being able to start, stop, restart agent pipelines

and always know where and why they broke

For that, a DAG and a watchdog turned out to be enough.

Sometimes you don't need more intelligence. Sometimes you just need control.